- Andrew Cotten

- Nov 2, 2025

Occasional reflections on hospitable moments with folks who just seem to get it.

I, like many other proud weirdos, attended Phish’s two-night run at Birmingham’s Coca-Cola Amphitheater this past September. It had been a decade since my last rodeo with the band at Oak Mountain, and after striking out in the ticket lottery, I figured it’d be another ten. But then my brother—who’d moved to Indiana last year—managed to score a fair pair for both nights. And truthfully, I was more excited about the reunion than the return. We've been going to jam band shows together since I was fourteen and he was eighteen, and this one felt earned.

Saturday was stellar--one for the ages, but by Sunday, a full slate of afternoon commitments had drained whatever battery I’d been running on. Lupus is funny that way: multi-day events always depend on how your flare-up decides to show up. Even as the show began, I knew I probably wouldn’t make it to the end.

Sure enough, around 10:00 p.m.—a good hour or so before the band packed it in—I was fading fast. Fading to the point that there may not have been much difference between me and the blissed-out Wookie wobbling into me like a shoreline tide. I bought a Coca-Cola, hoping it might shake something loose, but no use. The excitement that had carried me for months—and sustained a full-send Saturday—was running on fumes. So, I knew: it was time. I hugged my brother, saluted the band, and slipped out early.

I know, I know—“Fake Phish fan!” and “Name five songs!” Yeah, yeah, yeah...

I Charlie Brown’d my way outta there and walked down Carraway Boulevard, the main thoroughfare to the venue’s lone entrance. The herd of hippies hipsters I’d scurried in with earlier were still at the show, and the only folks on the road were either uninformed of the festivities or uniformed officers. As refreshing as it was to be able to spread my arms out or feel the cool breeze, it was oddly lonely, too: only minutes before, I was shoulder to shoulder with my brother grooving to the crowd-favorite, “What's Going Through Your Mind.” Now, I was alone.

I passed the “lot,” a nomadic space where concert-goers gather to reconnect, break bread, buy booze or Terrapin bandanas, or burn one down before the show. It was barren now, save those passed out beside nitrous tanks on a pillow of empty balloons. Past the Pop-Up Tent paradise, I passed pockets of security guards. They were cordial, but I imagined they were eager to get back home. Trey Anastasio, the Mad Hatter himself, wasn’t doing them any favors either: as he soloed with relentless repetition during “What’s the Use?”. Distance did the sound quality no favors either: the distinct notes that create order in chaos were muddied; it sounded more like Trey was tearing open wrapping paper than tickling the fretboard.

I turned right onto 13th Avenue North and made my way up the steep hill, with 22nd Street at the top. An empty grass lot on my left, the right was lined with high-pitched brick houses: each dark, its residents most likely already asleep—save one house.

Most of the lights in the front half of the house were on, and judging by the bright white-light, I doubt a single one was less than a hundred lumens. I noticed a lady sitting on the porch, spotlighted underneath the overhead lamp. I could only see her head and shoulders, but I could tell she was staring out onto the street while talking to someone else on the porch who was out of view.

Aware of how far the amphitheater’s sound carries—and how Phish (or any other band) might not exactly be what this community was hoping to hear as it falls asleep—I decided to express a little gratitude on behalf of tonight’s rotation of rabble-rousing concert-goers. Parallel to her steep ladder-like stairs, I shared some passing praise: “Evenin’, ma’am! You have a beautiful neighborhood—thank you for having me!”

She popped up from her seat, peered over the porch rail, and asked what I had said. I had to repeat it four or five times before she had quieted the dogs enough to receive it. And as soon as she returned from shushing and rushing them inside, Trey was at it again: a cacophonous dust cloud of diminished chords roared from the soda island across the sea as King Trey rallied his Wild Things for a rambunctious and rowdy rumpus.

She thanked me for the compliment and went on to say that she sits out there every night there’s a concert.

I asked if she stayed out there so she could hear the music.

“No, I wait and watch until everybody is back in their cars safe and sound.”

“That’s sweet of you, ma’am. Thank you. I know I feel better.”

Before I turned back to the climb ahead, I asked, “What’s your name, by the way?”

The overhead light that had illuminated her presence now obscured her expression; but I gleaned her demeanor from the cautious and guarded “Why? Who wants it?” she answered with.

“Oh, just me,” I said. “I thought I might say a little prayer thanking you. Maybe even write a little reflection—I do those sometimes for work, when I come across moments of super kind hospitality, and I’d love to write about you.”

She slapped the stone partition and said, “Oh, my! Are you a paper man?”

I said, “No, ma’am. I just like to write. Helps me think, process the day, ya know?”

She pressed her torso against the railing and leaned over the porch with authority. She pointed right at me—her arthritic finger suggesting I wasn’t alone—and said, “That’s good.” She leaned back, pressed her right hand to her breast, and said, “I’m Charlie.”

“I’m Andrew,” I returned. “Good night, Miss Charlie. Thanks again!”

I waved and walked on.

A step or two closer to my car, I heard her porch guest say, “Oooohhh. He’s gonna write about you!” followed with a surprised yet satisfied, “I know! Can you believe it?” And they both laughed, as if it was a trip to think that she, Miss Charlie—an elderly lady just sittin’ on her porch—was worth someone’s words.

I took one last look before the neighbors’ bushes blocked my view. Moths moved in ribbon rings as bugs bounced against the glowing globe above her. But she hadn’t moved: she was still facing Carraway Boulevard, still waiting on the others.

I don’t know how many shows she’s listened to from that porch, or how many wanderers she’s watched over as they meander safely back to their cars. But I know this: when the lights go out and the amps shut down, Miss Charlie is still on the clock.

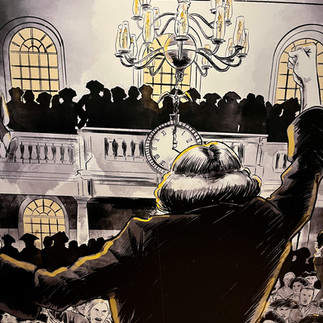

At the summit of 22nd, I was finally high enough to see the St. James steeple that Miss Charlie’s hill-top two-story had hidden earlier. Its sudden appearance made it look as if it had cracked through the roof and cut into the sky. The fog-machine haze and haphazard stage lights polluted the night, blurring the spire’s definition, but not its presence. It stood like a quiet sentinel.

I looked back at the hidden porch—the light humming overhead. I couldn’t see her now, but I’m certain she was watching, willing to stay up long enough until the last of us made our way home.

Maybe hospitality isn’t always the door flung open…sometimes it’s leaving the light on and looking after folks.

I don’t know if Hospitality, Lately is a blog, a series of Google Reviews, private letters, or just one of those weird writerly habits I can’t shake. But I know this: writing these helps me notice what matters. Helps me remember that high-quality customer service doesn’t have to be customer-facing. And that the kind of kindness I want to practice in my classroom sometimes shows up in the quiet, sidelong care of strangers.

Like Miss Charlie.